The One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) was signed into law earlier this month, with sweeping changes to taxes, immigration, defense, energy, health, and more. Since then, there has been widespread moral outrage over the bill, especially in light of cuts to Medicaid, cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and increased spending for ICE. Plenty of people, of course, are talking about other aspects of the OBBB, but these three subjects seem to account for a lion’s share of the moral outrage.

Much of this outrage has been targeted at politically conservative Christians, given their significant role in the election of President Trump (who spearheaded the bill). Whether it’s coming from progressive nonbelievers or progressive Christians, the message is the same: The OBBB is contrary to biblical teachings on caring for the poor and marginalized, and those who support it should be ashamed. For example, headlines like these abound:

- From Yahoo News: “Opinion: Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill is at odds with the teachings of Jesus”

- From Baptist News Global: “Faith leaders decry ‘big beautiful bill’ as immoral and un-Christian”

- From Newsweek: “How ‘Hell Bent’ Evangelical Theology Fuels America’s Cruel Politics” (the author says the bill is “historically cruel” because it will “deepen inequality, gut health care and food aid for needy families, and escalate Trump’s war on vulnerable immigrants”)

- From the National Catholic Reporter: “Editorial: One big shameful bill” (the author calls the OBBB one of the “most immoral pieces of legislation in recent memory”)

My purpose in this article is to show that this narrative reveals a widespread confusion and naivety regarding what a biblical view of government actually is.

To be very clear, my purpose here is not to defend the OBBB—I’m not even making a statement about whether I personally think the bill is a good one or not.

But whatever a person may believe about the OBBB itself, Christians should be able to think biblically and logically about the nature of the current moral outrage.

Here are five points everyone should understand.

1. There is a biblical difference between the responsibility of individuals and the responsibility of governments.

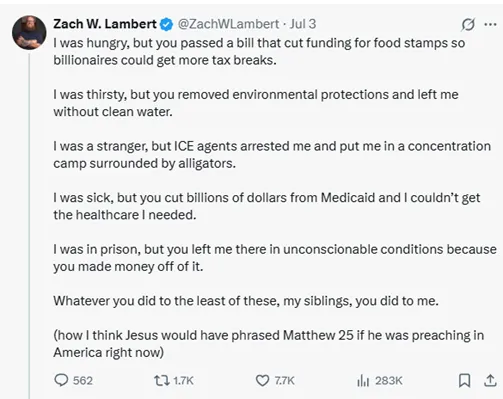

Progressive Christians often conflate these two responsibilities (as do nonbelievers who indiscriminately use Scripture to chastise politically conservative Christians for presumed hypocrisy). They pull verses from the Bible that speak of how individuals are to be generous and apply that to governments. Here’s one example from progressive pastor Zach Lambert on X.

Lambert is referencing Matthew 25:35-40, in which Jesus speaks of the final judgment. In this passage, those who are righteous will have fed the hungry, gave drink to the thirsty, welcomed the stranger, clothed the naked, visited the sick, and visited the imprisoned as an outworking of their faith. They will inherit eternal life, whereas those who did not do these things will “go away into eternal punishment.”

Given the Judgment Day context, this passage is obviously about individual actions, not those of governments.

While Lambert acknowledges at the end of his post that this is what he “thinks” Jesus would have said in America today, it’s an unjustified extrapolation given the original context. There are many passages like this in Scripture that are clearly speaking to personal generosity and not the functioning of government (for example, 2 Corinthians 9:6–7, Acts 20:35, Luke 6:38, James 2:15–17, or 1 Timothy 6:17–19). You can’t simply assume that any charge to individuals is naturally transferrable to the government as an institution.

That said, I’m not suggesting the Bible has nothing to say about government responsibility or that what it does say doesn’t overlap in any way with the nature of individual responsibility. Rather, I’m saying that in order to determine what a biblical view of government is, we need to look at passages that are applicable to that specific context.

This brings us to the next point.

2. The biblical responsibility of government is to promote good and restrain evil.

Unfortunately, churches today rarely disciple their people on how to think biblically about government and the Christian’s responsibility in the political sphere, so misunderstandings about the interaction of faith and politics are pervasive—in many cases to the detriment of societal good. I address this at length in my newest book, When Culture Hates You: Persevering for the Common Good as Christians in a Hostile Public Square. In brief, here are a few key points Christians should understand about the biblical role of government:

- In the Old Testament, the first mention of what could be considered civil government is in Genesis 9:5-6, when Noah and his family exit the ark after the flood. God says he will require a reckoning for murder to be carried out by human beings: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image.”

- The basic principle that mankind is responsible for executing punishment for certain actions is assumed throughout the rest of the Bible. For example, in the Old Testament, when God calls out nations for not practicing righteousness and justice, that assumes an expectation that civil leaders are responsible for promoting what is good and restraining what is evil (see Proverbs 31:8-9; Daniel 4:27; Amos 1—2; Obadiah).

- In the New Testament, this expectation is most explicitly stated in Romans 13:1-7. Three key takeaways from this passage include: 1) civil rulers receive their authority from God Himself, and as such are His servants; 2) civil rulers should be God’s servants for promoting the good (note that whereas Genesis 9:5-6 explicitly affirms only civil punishment, Romans 13:1-7 also explicitly affirms the civil role of promoting the good); and 3) civil rulers have the authority to bear the sword as avengers on God’s behalf (i.e., they are to restrain evil).

I suspect that most progressive Christians condemning the OBBB changes would be in full agreement with this point that the Bible teaches the government should promote good and restrain evil. They would say, “Yes, exactly! This is a matter of justice for the poor, to provide health care and food—this is the good the government should be promoting; sickness and hunger are evils to restrain.”

While that sounds good, this kind of thinking doesn’t go far enough to consider the complexities of my next point.

3. The fact that there are finite government resources means there will necessarily be tradeoffs between goods.

As I explain in When Culture Hates You,

“[Biblical] specifics aren’t given on the various forms of the good that God’s servants should promote, so even among Christians who agree this is a role of government, there will always be some disagreements. In modern society, for example, should government provide the good of healthcare for all? How about the good of public education? Or the goods of national security, infrastructure, or national parks? In at least some sense, all of these examples could be defined as a good. Yet we all recognize that there’s a limit to what government can provide because financial resources are finite; we can’t have every good we might theoretically want. So while it’s a biblical principle that civic governments should indeed promote the good, Christians will still inevitably disagree on how to prioritize individual goods their government might pursue.”

More succinctly: The Bible never says the government is responsible for providing every possible good and the government doesn’t have infinite money to spend.

The U.S. currently has a $36 trillion debt. Just as a family needs to budget in order to live within their means, a nation must do the same. The government simply can’t provide every good thing.

4. Cutting back on goods is therefore not necessarily “immoral” or “unchristian.”

The presupposition of many who are speaking out against Medicaid and SNAP cuts, for example, is that taking anything away from those in need is inherently unjust. It makes for emotionally powerful appeals (“The OBBB is taking health care and food away from millions!”), but consider the implication of that presupposition. It would mean that no matter how financially imprudent it might be for the government to begin offering a good in the first place, it’s always morally wrong to later take it away.

But there are numerous ways people are adversely affected by out-of-control government debt—higher interest rates, inflation, economic instability, and much more. Adding a social program isn’t an act of justice simply by virtue of the fact it will benefit some group of people; it could end up hurting more people than it helps given the longer term impact on the economy. And if a nation is held to the standard that it’s always morally wrong to take something away once it’s been given in the first place, it can never rectify poor decisions of the past without people claiming injustice.

5. Limiting the distribution of goods to those who are legally in a country is also not necessarily “immoral” or “unchristian.”

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned the fact that part of the moral outrage about the OBBB is increased spending for ICE—a double-edged outrage at 1) deporting those considered to be marginalized and 2) doing so using money taken in part from programs like Medicaid and SNAP. The subject of how Christians should view illegal immigration and enforcement is beyond the scope of this article, but it’s worthwhile to point out that this subject, too, is a question of how to prioritize the various goods a government might pursue.

A nation cannot feed, clothe, shelter, educate, and provide health care for every person who desires such goods from anywhere in the world.

That nation will run out of resources quickly, leaving everyone destitute.

Thus, there must be limits—limits to the goods government can provide (see point 3) and limits to who can receive them.

Contrary to popular sentiment, recognizing that these limits necessarily exist is not “unchristian”; it’s reality. That doesn’t mean there are no necessary principles Christians should take from Scripture regarding immigration. This article does an excellent job of breaking down what several of those principles are. But it does mean that, ultimately, immigration is just one more subject within the broader conversation of how a nation should best prioritize competing goods given existing constraints.

As I said at the beginning, I’m not here to defend the specific content of the OBBB. But my hope is that Christians will think more clearly about the biblical role of government when having these conversations. Progressives don’t hold a more biblical view simply by supporting every social program for every person in the world in the name of Jesus, but they do hold the view that sounds better on the surface. In a world of emotional social media sound bites, it’s more important than ever to understand the difference.